Week 4

Neo-Assimilation Theory

SOCI 231

Lecture I: September 23rd

A Quick Reminder

Response Memo Deadline

Your second response memo—which has to be between 250-400 words and posted on our Moodle Discussion Board—is due by 8:00 PM today.

Questions?

Do any of you have questions about the class?

This Week’s Focus —

Neo-Assimilationism

A Reminder

Straight-Line Assimilation (Stylized)

A Modern Alternative?

Neo-Assimilation Theory (Stylized)

A Modern Alternative?

Neo-Assimilation Theory (Stylized)

A Question

Broadly speaking, why do Groups A, B and C follow different trajectories? Think of proximate and distal mechanisms.A New Institutionalist’s Assimilation Theory

— Richard Alba and Victor Nee

Assimilation Theory, Old and New

Chapter 2 of Remaking the American Mainstream

In Chapter 2 of Remaking the American Mainstream,

Alba and Nee (2003) spend the first 18+ pages reviewing existing treatments of assimilation.

Assimilation Theory, Old and New

Chapter 2 of Remaking the American Mainstream

In their review, Alba and Nee (2003, 17–35) engage with a series of classical contributions to the assimilation canon, including —

The early theories of Robert E. Park and other Chicago School sociologists (Park 1914; Park and Burgess 1969).

W. Lloyd Warner and Leo Srole’s The Social Systems of American Ethnic Groups (Warner and Srole 1945).

Milton Gordon’s Assimilation in American Life (Gordon 1964).

Assimilation Theory, Old and New

Chapter 2 of Remaking the American Mainstream

We’ve read many of these pieces!

Assimilation Theory, Old and New

Chapter 2 of Remaking the American Mainstream

To fully apprehend neo-assimilation theory (Alba and Nee 2003; Nee and Alba 2013), we need to engage with one lesser known piece of scholarship, too.

Ethnic Stratification

— Tomatsu Shibutani and Kian Kwan

Alba and Nee’s Review(s)

Shibutani and Kwan’s (1965) book was not assigned.

If you want to peruse Ethnic Stratification: A Comparative Approach, you can access a free version here.

Shibutani and Kwan’s Treatment

According to Alba and Nee

The starting point of their analysis was the assertion that genetic differences between groups, if they even exist, cannot explain the social distances between them. Instead, differences giving rise to social distances are created and sustained symbolically through the human practice of classifying people into ranked categories.

(Alba and Nee 2003, 31, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Shibutani and Kwan’s Treatment

According to Alba and Nee

Their approach emphasized the cognitive dimensions of intergroup relations and the causal significance of beliefs shaping perceptions of social distance between majority and minority groups. In their approach, it is the reduction of social distance stemming from institutional change that cumulatively enables the way for assimilation of racial minorities.

(Nee and Alba 2013, 358, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Shibutani and Kwan’s Treatment

According to Alba and Nee

Social distance is the linchpin concept in the explanation of the color line that segregates minorities and impedes assimilation. By social distance, Shibutani and Kwan refer to the subjective state of “nearness felt to certain individuals,” not physical distance between groups. In their account, change in subjective states—reduction of social distance—precedes and stimulates structural assimilation.

(Alba and Nee 2003, 31, EMPHASIS ADDED)

A Question

Is this consistent with Gordon’s (1964) framework? Why or why not?Shibutani and Kwan’s Treatment

According to Alba and Nee

For Shibutani and Kwan, a stable system of ethnic stratification is embedded not just in informal arrangements—social norms, customs, and conventions operating at the micro-sociological level—but also in an institutional order in which the dominant group upholds its position and privileges through control of formal institutions, the state, and coercive forces. Thus, the subordination of ethnic minorities is maintained not merely by moral consensus but ultimately by institutionalized power and outright coercion.

(Alba and Nee 2003, 32, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Shibutani and Kwan’s Treatment

According to Alba and Nee

In most … cases … the assimilation of racial minorities occurs only incrementally as social distance is gradually reduced and the color line begins to break down. The mechanisms that bring about the reduction of social distance stem from structural changes that occur at the macro level. In the absence of such changes, ethnic stratification orders tend toward stable equilibrium. In other words, the segregation of racial minorities into ethnic enclaves would persist indefinitely in the absence of exogenous change.

(Alba and Nee 2003, 33, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Shibutani and Kwan’s Treatment

According to Alba and Nee

The most immediate source of a decline in social distance, Shibutani and Kwan assert, occurs when institutional change stimulates the introduction of new ideas that challenge values and cultural beliefs previously taken for granted, as in the discrediting of white supremacist ideologies in the postcolonial world, and a “transformation of values” ensues.

(Alba and Nee 2003, 34, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Shibutani and Kwan’s Treatment

Affordances and Key Insights

A finer appreciation of contingency — that is, disparate group trajectories.

A multilevel framework attuned to the relationships between the micro, meso and macro — or individuals, “groups,” and the state apparatus.

Acknowledgement of exogeneous shocks (e.g., technological advances) as a mechanism of assimilatory change.

Acknowledgement that assimilation is not inevitable.

Group Discussion I

Shibutani and Kwan vis-à-vis Gordon

Neo-Assimilation Theory:

The Building Blocks

Approach to Causation

In constructing a theory of assimilation, we follow the “new realists” in the philosophy of science in moving away from the “covering law” approach to explanation associated with classical positivism. Causation, instead, is identified as a central cluster of diverse and specific processes conceived as mechanisms that produce or generate the phenomenon to be explained.

(Alba and Nee 2003, 35, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Approach to Causation

Our aim is to explain assimilation as a process of cumulative causation driven by a repertoire of mechanisms operating at the individual, network, boundary, and institutional levels. We assume that no single causal mechanism explains the mode of immigrants’ accommodation to their host society; instead a repertoire of mechanisms operating at different analytical levels is involved. In combination, and cumulatively, they shape the trajectories of adaptation of immigrants and their children.

(Nee and Alba 2013, 360, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Approach to Causation

The mechanisms proposed are general to social behavior and fall broadly within two groups: the proximate causes that operate at the individual and social network levels, shaped by the specific forms of capital immigrants possess, and the distal, often deeper, causes that are embedded in large structures such as the institutional arrangements of the state, firm, and labor market.

(Nee and Alba 2013, 360, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Adopting the New Institutionalism

The neo-assimilation framework is predicated on the

new institutionalism.

Adopting the New Institutionalism

[N]ew institutionalists in the social sciences generally presume purposive action on the part of individuals, albeit under conditions of incomplete information, inaccurate mental models, and costly transactions. Such conditions are common to everyday social and economic transactions. Although the new institutionalist paradigm rejects the basic assumptions of neoclassical economics, it remains committed to the choice-theoretic tradition of explanation in the social sciences.

(Nee 1998, 1, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Adopting the New Institutionalism

In the new institutionalist approaches, explanations for institutional change generally refer to causal mechanisms embedded in the purposive action of individual and corporate actors, which in turn are shaped by cultural beliefs, relational structures, path dependence, and changing relative costs.

(Alba and Nee 2003, 36, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Adopting the New Institutionalism

Okay, but what do “institutions” refer to in concrete terms?

Adopting the New Institutionalism

Institutions, defined as a web of interrelated norms, formal and informal, govern social relationships. As Durkheim argued, they serve as constraints shaping social and economic exchange at all levels of society. Institutions are not merely constraints, however, but are also resources that make possible the achievement of goals not otherwise attainable.

(Alba and Nee 2003, 36, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Adopting the New Institutionalism

How do individuals interface with these institutional webs?

Adopting the New Institutionalism

Agents act according to mental models shaped by cultural beliefs —customs, social norms, law, ideology, and religion—that mold perceptions of self-interest. They follow rule-of-thumb heuristics in solving problems that arise, and make decisions in the face of uncertainty stemming from incomplete information and the risk of opportunism in the institutional environment. For this reason, new institutionalists view rationality as context-bound and contingent in contrast to the rationality assumption of neoclassical economics.

(Alba and Nee 2003, 37, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Adopting the New Institutionalism

[C]ontext-bound rationality views agency as stemming from choices made by actors according to perceptions of costs and benefits embedded in the institutional environment. It assumes limited cognitive ability on the part of actors … Adaptations based on unintended consequences of action that result in success or rewards also fall within the purview of context-bound rationality. If an unintended consequence results in success, actors are likely to repeat the action. Similarly, if the informal norms of a close-knit group contribute to producing unintended beneficial outcome, the group will reinforce these norms.

(Alba and Nee 2003, 37–38, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Group Discussion II

New Institutionalism and Assimilation

In groups of 2-3, discuss how you might make sense of immigrant assimilation using the new institutionalism as a guide.

Hint

The work of Shibutani and Kwan (1965) may be instructive.Lecture II: September 25th

Review

A Question

How did Alba and Nee incorporate the insights of Shibutani and Kwan?Proximate Mechanism I —

The Actions of Individuals

Purposive Action

A satisfactory theory of assimilation must, at the individual level, conceptually incorporate agency stemming from purposive action and self-interest and provide an account of the incentives and motivation for assimilation.

(Alba and Nee 2003, 39, EMPHASIS ADDED)

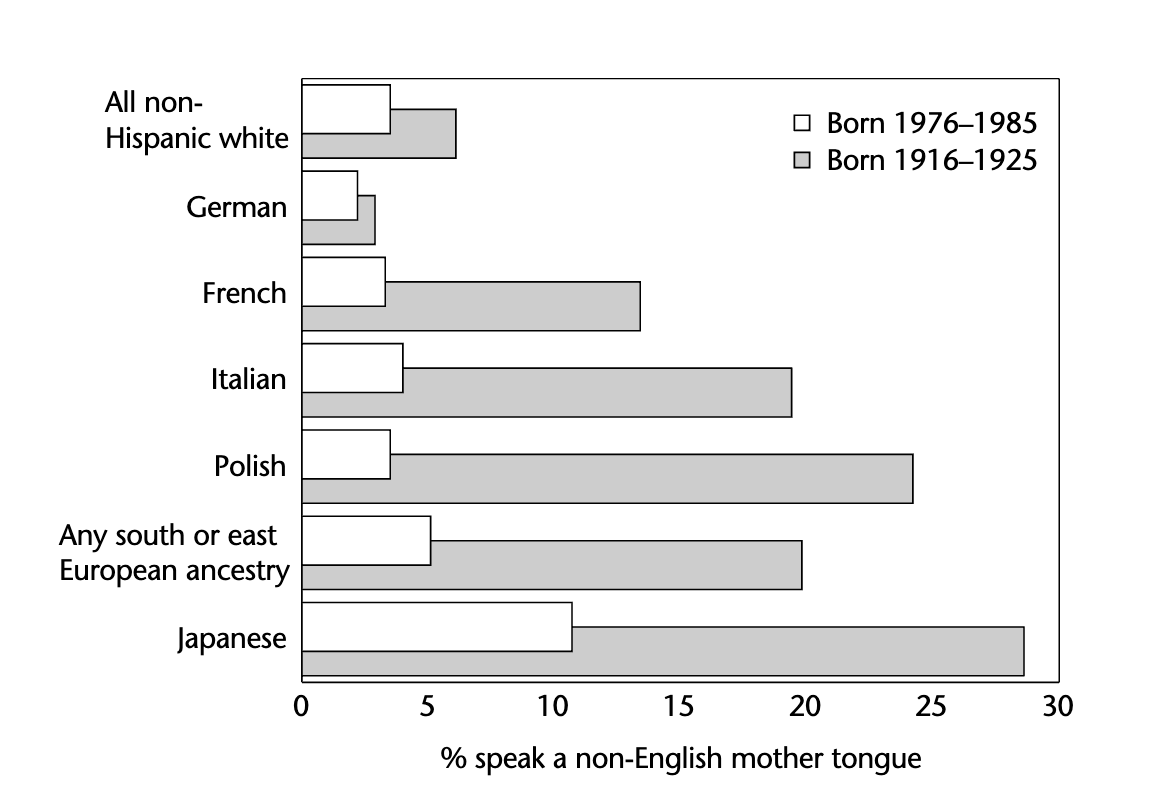

Purposive Action

An Example

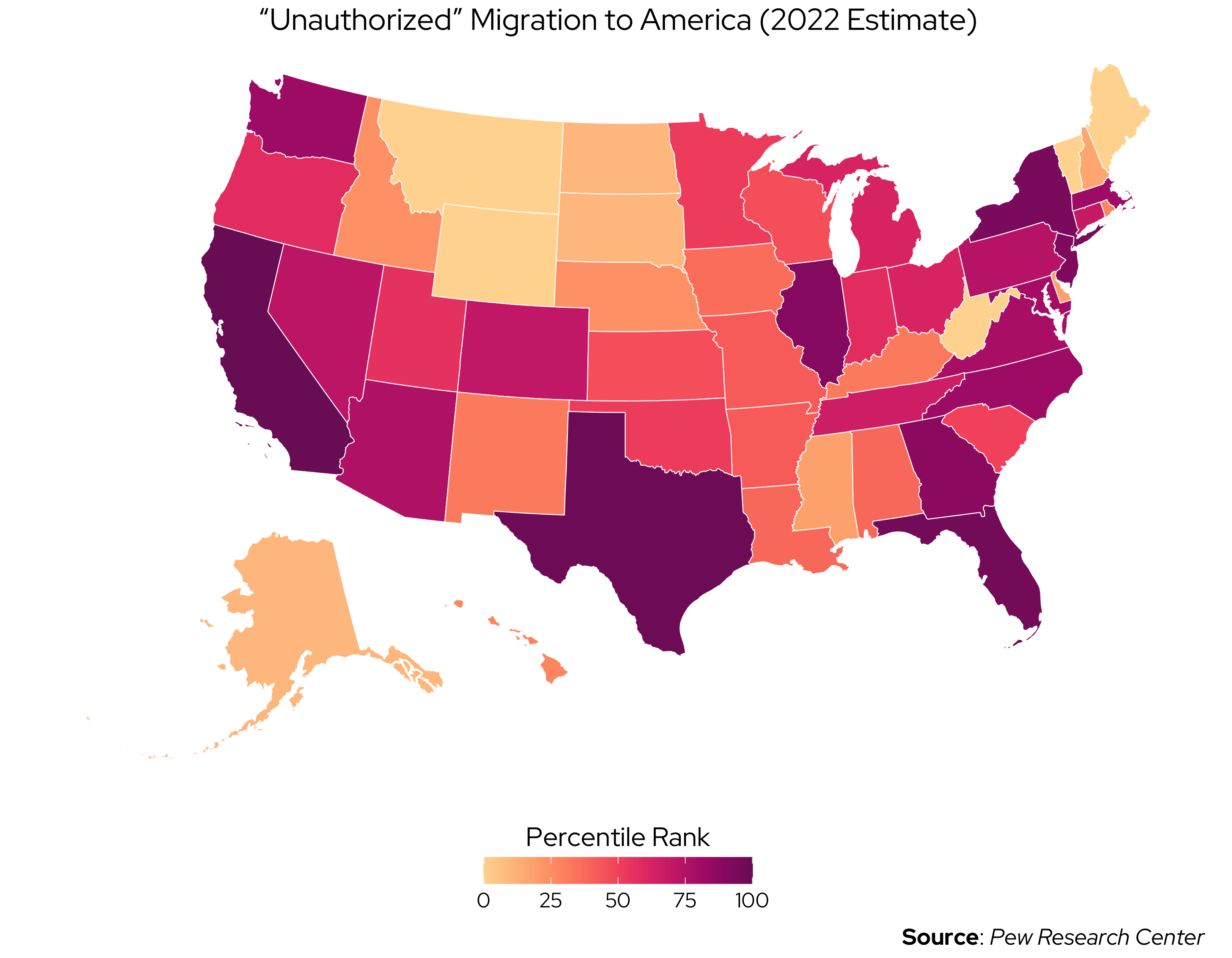

Note: Data comes from the Pew Research Center.

Purposive Action

An Example

Purposive Action

In their adaptation to life in the United States, many descendants of immigrants face choices in which the degrees of risk and of benefit are similarly hard to gauge; it is also usually the case that these choices involve long-term consequences that are unforeseeable.

(Alba and Nee 2003, 41, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Purposive Action

In contemplating the strategies best suited to improve their lives and those of their children, immigrants and the second generation weigh the risks and potential benefits of “ethnic” strategies, dependent on opportunities available through ethnic networks versus “mainstream” ones, which involve the American educational system and the open labor market.

(Alba and Nee 2003, 40–41, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Purposive Action

There are, of course, constraints.

Purposive Action

For those with low levels of human/financial capital—and for the undocumented writ large—ethnic strategies will be much likelier.

Purposive Action

For those with more resources,

mixed strategies may be more common.

Purposive Action

Individuals striving for success in American society often do not see themselves as assimilating. Yet the unintended consequences of practical strategies and actions undertaken in pursuit of familiar goals—a good education, a good job, a nice place to live, interesting friends and acquaintances, economic security—often result in specific forms of assimilation.

(Alba and Nee 2003, 41, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Purposive Action

Figure 3.1 from Alba and Nee (2003)

Purposive Action

[T]he search for a more desirable place to live—with good schools, safe streets, and opportunities for children to grow up away from the seductions of deviant models of behavior—leads immigrant professionals and entrepreneurs to move to the suburbs (if and when socioeconomic success permits this) … One consequence, whether intended or not, is increased interaction with families of other backgrounds; such contacts tend to encourage acculturation, especially for the children.

(Alba and Nee 2003, 41, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Purposive Action

Purposive Action

Associated with acculturation are culturally codified notions of appropriate behavior which, when learned, serve as cues to others as to an individual’s level of cultural and social competence. Such competence contributes to reducing social distance by signaling behavioral attributes that appear familiar and trustworthy.

(Alba and Nee 2003, 42, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Proximate Mechanism II —

Network Dynamics

Network Mechanisms

What are network mechanisms?

Network Mechanisms

“[T]he social processes that

monitor and enforce norms within close-knit groups.”

(Alba and Nee 2003, 42, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Network Mechanisms

(An) analytically tractable approach to understanding the causal properties of networks and norms is to focus on the social exchange mechanisms that enable actors to engage in joint action as a means to achieve collective goals. In close-knit groups, the mechanisms are the social rewards and punishments.

(Alba and Nee 2003, 42, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Network Mechanisms

Norms are the informal rules that provide guidelines according to which joint action in close-knit groups or social networks is sustained. They arise from the problem-solving activity of individuals striving to improve their chances for success through cooperation. Members of a close-knit group or social network will informally encourage one another to engage in cooperative behavior by jointly enforcing its norms. Individuals cooperate because not only are their interests linked to the success of the group but their identity is as well.

(Alba and Nee 2003, 43, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Network Mechanisms

The norms of close-knit groups or networks do not have a specific normative or moral valence.

A Question

How does the story of Chinese-origin migrants in the Mississippi Delta (1870-) drive this point home?Network Mechanisms

The experience of the Mississippi Chinese is an exceptional case of collectivist assimilation involving a close-knit community in the extreme circumstances imposed by racial segregation in the South. More commonly, assimilation occurs through a path-dependent process involving interaction between collectivist and individualist modes of adaptation.

(Alba and Nee 2003, 45, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Forms of Capital

The forms of capital brought by today’s immigrants differ significantly both within the same immigrant stream and among ethnic groups. Exemplifying the former, immigration from Mexico, though made up overwhelmingly of manual laborers from rural towns and villages, also includes a large number of urban professionals and technical workers.

(Alba and Nee 2003, 46, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Forms of Capital

At the same time, ethnic groups can be seen as broadly differentiated from one another on the basis of the forms of capital they typically tend to bring. At one end of the continuum are the East Indian, Korean, and Filipino immigrant groups, which include high proportions of professionals and technical workers holding college or postgraduate degrees. At the other end are the low-wage laborers from Mexico who come generally with a primary school education.

(Alba and Nee 2003, 46, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Forms of Capital

Today’s immigrants also arrive with varying amounts of financial capital, which can be important in easing the transition to workaday lives …

By contrast to middle- and upper-middle-class immigrants, labor migrants commonly have no financial capital to speak of. Those who have to borrow money to cover the cost of undocumented immigration often unwittingly become trapped in a modern form of indentured servitude, working for ethnic entrepreneurs who exploit them as cheap labor.

(Alba and Nee 2003, 46, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Forms of Capital

So, what does all of this mean?

Forms of Capital

Assimilation into the mainstream society is affected not just by the social, financial, and human capital of immigrant families but also by the ways individuals use these resources within and apart from the existing structure of ethnic networks and institutions.

(Alba and Nee 2003, 47, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Forms of Capital

Some Examples

Members of the two English-speaking groups—Filipinos and Indians—have found jobs in the mainstream labor market, reside in mixed residential neighborhoods, and have shown no special proclivity for self-employment or interest in building an ethnic enclave economy.

(Alba and Nee 2003, 47, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Forms of Capital

Some Examples

By contrast, Korean immigrants, who do not come from a culture where English is widely spoken, optimize their human and financial capital by investing in small businesses and developing an ethnic economy in which their native cultural competence is advantageous.

(Alba and Nee 2003, 47, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Institutional Constraint

Institutional Mechanisms

The same proximate mechanisms can ignite segregating or blending processes conditional on institutionalized incentives.

Institutional Mechanisms

A Brief Aside

A critique of the oppositional norms thesis.

Institutional Mechanisms

To be sure, there are many other institutional pathways to segregating vis-à-vis blending processes.

A Question

How did segregating dynamics emerge among Japanese Americans prior to the Second World War?Institutional Mechanisms

An Example

On the eve of the Pacific war, Japanese Americans were among the most socially isolated ethnic groups in America. The structure of opportunity and incentives for the second generation was nearly entirely bounded within the ethnic economy by virtue of their exclusion from the mainstream.

(Alba and Nee 2003, 52, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Institutional Mechanisms

An Example

It was only after the demise of the ethnic economy, undermined by the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, that the causal dynamic reinforcing racial segregation was finally broken. During the postwar era, Japanese Americans assimilated rapidly according to the individualistic pattern, following the ensuing decline of societal hostility, shifts in the occupational structure stemming from sustained economic growth, and the institutional changes arising from the civil rights movement.

(Alba and Nee 2003, 52, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Institutional Mechanisms

What does this example tell us about the causal properties of institutional mechanisms?

Institutional Mechanisms

Institutional mechanisms constitute the deeper causes insofar as they determine whether the proximate mechanisms—purposive action and network mechanisms—advance blending or segregating processes … (Specifically) the institutional mechanisms of monitoring and enforcement of formal rules of the state organizations constitute a potent causal force.

(Alba and Nee 2003, 52–53, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Institutional Mechanisms

[I]n the post–civil rights era, the institutional mechanisms for monitoring

and enforcing federal rules have increased the cost of discrimination in nontrivial ways …But the more important institutional changes are those that have not only increased the cost of discrimination but also led to changes in values. One of these is the remarkable decline in the viability of racist ideologies since the end of World War II.

(Alba and Nee 2003, 52–57, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Institutional Mechanisms

Note: Data comes from the General Social Survey.

Boundaries

Boundary Mechanisms

Because social boundaries are by their nature two-sided, the great utility of the boundary conception within assimilation theory is that it brings attention to the powerful role of the majority population in affecting the life chances of minority individuals and thus influencing the intuitive calculations that immigrant-origin individuals make in assessing the possible risks and benefits of an assimilation strategy.

(Nee and Alba 2013, 367, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Boundary Mechanisms

Bright boundaries involve a distinction that is unambiguous, so that individuals know at all times which side of the boundary they are on. Blurred boundaries allow for modes of self-presentation and social representation that place individuals in ambiguous zones with respect to the boundary.

(Nee and Alba 2013, 367–68, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Boundary Mechanisms

In the case of a bright boundary, assimilation takes the form of individualistic boundary crossing.This process is likely to be experienced by the individual as something akin to a conversion … with all of the social and psychic burdens a conversion process entails—growing distance from peers, feelings of disloyalty, and anxieties about acceptance.

(Nee and Alba 2013, 368, EMPHASIS ADDED)

A blurred boundary, by contrast, means that individuals are seen as simultaneously members of the groups on both sides of the boundary or that sometimes they appear to be members of one and at other times members of the other. Under these circumstances, assimilation may be eased insofar as the individuals undergoing it do not sense a rupture between participation in mainstream institutions and familiar social and cultural practices and identities.

(Nee and Alba 2013, 368, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Putting It All Together

Key Propositions

| Mechanism | Proposition(s) |

|---|---|

Purposive Action |

If perceived opportunities are more extensive and plentiful in the mainstream than in ethnic enclaves, then purposive action of immigrants and their children will be aimed at optimizing returns to investment in human and cultural capital in the mainstream society, even in the face of opposition to their assimilation by individual members of the majority and minority groups. |

Networks |

In general, when discriminatory barriers block an individualistic pattern of social mobility, assimilation, when it occurs, depends on ethnic collective action. |

Institutions |

1) If society’s constitutional rules and their enforcement by the state extend formal equality of rights to all citizens, and 2) if political actors signal credible commitment to reinforcing cultural beliefs and formal rules of equality of rights, then immigrants and their children entitled to full citizenship are likely to choose a course of social action that increases their likelihood of assimilation. |

Boundaries |

1. The nature and extent of assimilation depend on the nature of the boundary separating an immigrant-origin minority from the majority group. A bright boundary favors individualistic, abrupt assimilation undertaken by a selective subgroup; a blurred boundary, a gradual assimilation by larger numbers who perceive themselves in terms of hyphenated identities and experiences. |

Text drawn directly from Nee and Alba (2013)

Group Discussion III

Interpreting This Stylized Summary

The End (Until Monday)

References

Note: Scroll to access the entire bibliography